At the end of last year I travelled again to my favourite (my wife strongly disagrees, so I am there rather rarely- and alone) holiday destination: La Chaux-de-Fonds and the surrounding «watch towns». One of the reasons for this visit was a stopover at Lundis Bleus, an independent watchmaking brand, specialising in enamel (and stone) dials.

As it happens, the famous MIH (the International Watch Museum in La Chaux-de-Fonds) hosted a small but very well made a special exhibition on «enamel in watchmaking» just at the same time.

So as an introduction, I may just quote the labelling of a cabinet of that exposition:

“The journey to the furnace

More than a simple decoration, enamel is a complex and challenging technique, which requires patience and meticulous attention to detail. Its quality rests on two key elements: the raw material and mastery of the processes, in other words, preparing the recipe and firing. Enamel is a glass whose colour depends on the addition of different metal oxides. Cobalt colours the glass blue, copper turns it red, zinc makes it yellow, and so on.

Although enamelling essentially consists of applying coloured glass powder to a metal substrate to be fired in a furnace, the process of creating an enamelled piece comprises many steps and different facets. Based on various sources of inspiration, many sketches are drawn before obtaining a design which can serve as a template. Before beginning the work, the artisan must familiarise themselves with the various properties of the enamel: its colour, its opacity or the temperature at which it fuses.”

Inside the MIH: Ancient equipment, mortar and pestle, glass, recipe books etc.

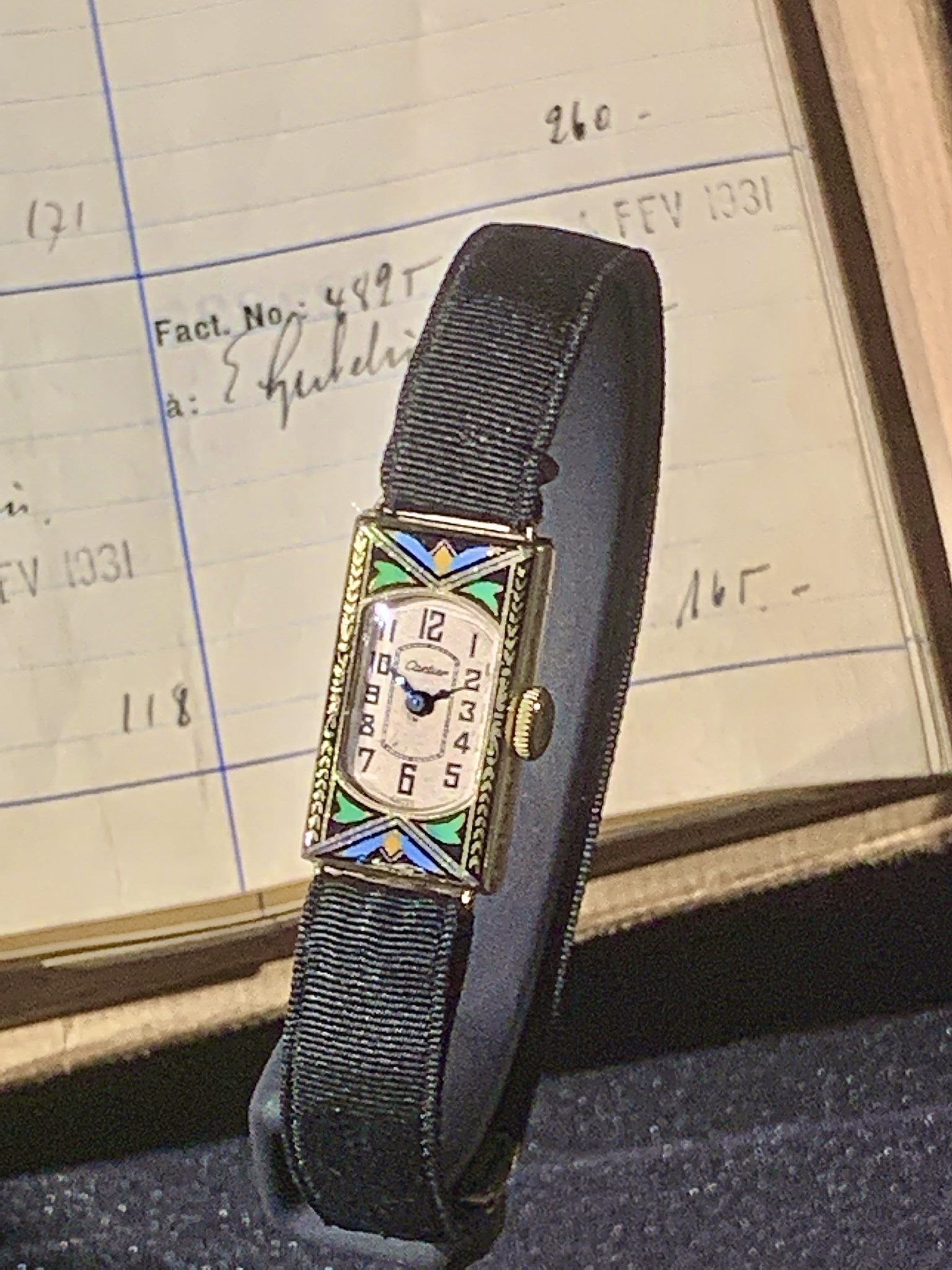

Inside the MIH: a Cartier art nouveau watch with an enamel case

I met Bastien Vuilliomenet, the man behind Lundis Bleus, in his workshop right in the picturesque old town of Neuchâtel, just 20 km south of La Chaux-de-Fonds.

(As you can kind of see from the pictures below, his modern workshop is also located in historic rooms. This alone is worth a visit …)

Lundis Bleus is basically – in the most positive meaning of the word – a one-man-show (“I also do the cleaning here”). Having said this, with Bastiens background (he is a graduated watchmaker with a degree in product design and a vast variety of experiences in the industry) he is well equipped with the tools of the trade to handle not only the enamel side of things (on which we focus here), but also the design, watchmaking, marketing, etc.

So let’s look into the making of a Lundis Bleus watch … but bear with me, we are still not ready to consider the enamelling.

As with any good painting, the frame must both show off the picture and be a work of art in its own right. So have a look at the watch case:

It consists of only two part and – unusually – it’s the case back where the lugs are attached (this actually reminded me of the similar case construction of ochs und junior watches where this proves to me to be very comfortable).

The case itself is then mounted from the top and secured with four screws. This also leads to a small slit between the lugs and the case, resulting in a kind of «light» look (this again reminds me distantly of the lugs of another watch – which was launched after the Lundis Bleus design btw – the AP CODE 11.59).

Can you see on my (lousy, sorry) picture that the buckle resembles the lines of the lugs? It’s these kinds of details that get me interested in a watch or a brand!

The case itself is formed like a ball or a «soft» truncated cone, sitting very comfortably on the wrist. The crown is also far from being off the shelf, its special (again a truncated cone) shape reduces the potential pressure on the wrist.

Case

Case and buckle

But let’s concentrate on the star of the show, the dial. How does a dial like this come into being? Step one is the making of what I would call the dial base.

Dial History

First of all the basic dial is manually punched out of a solid piece of sliver. While the progression to step 4 (from the left) are quite easy to comprehend, the next procedure (the fifth «dial» from the left) involves various measures.

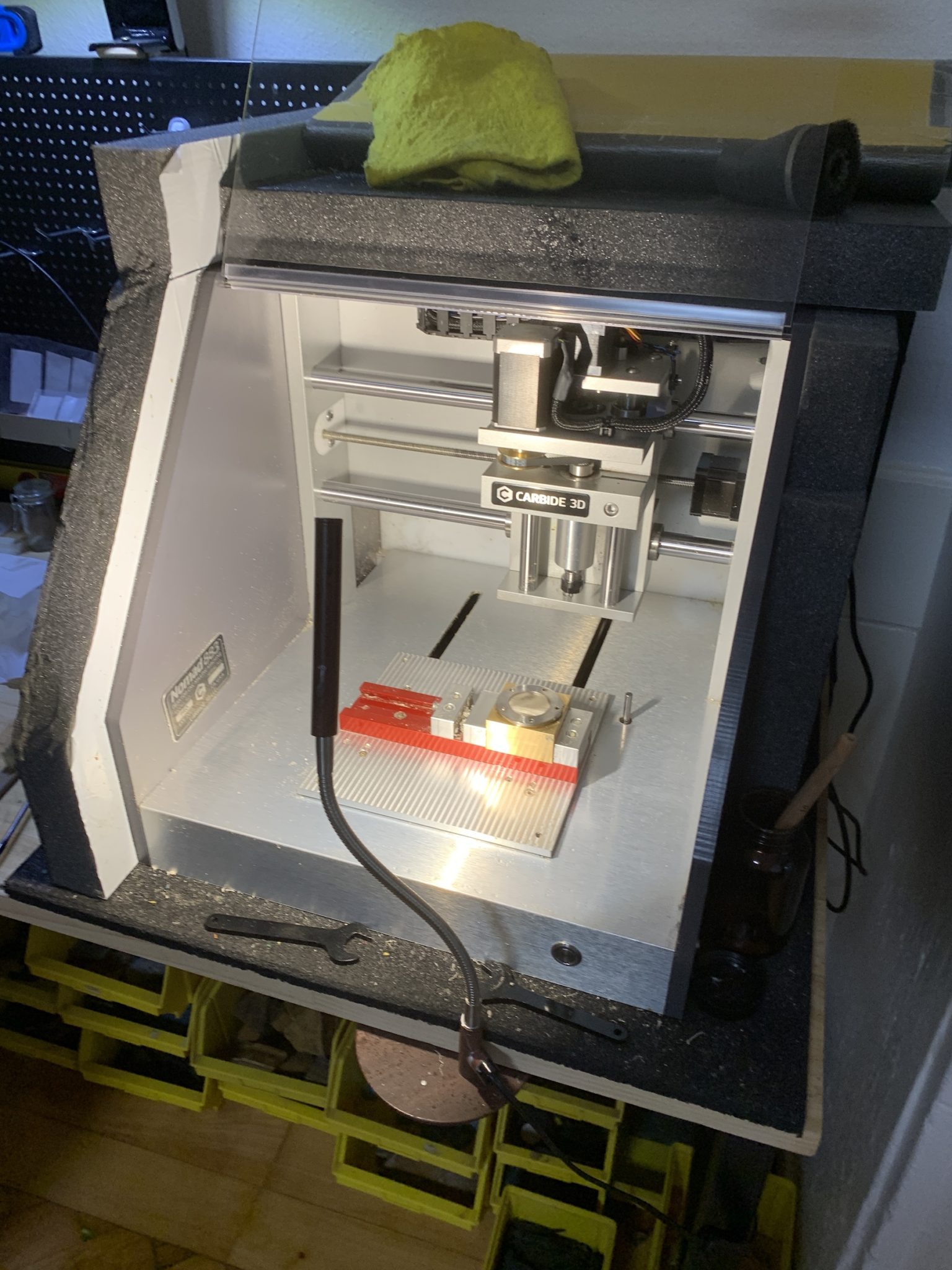

In order to prevent the enamel vom cracking due to different temperature coefficients, each dial needs some (white, as you can see on the picture; so called counter-) enamel on the back – where you eventually never see it. This, however, would make the dial thicker. Therefore Bastien mills out the back of the dial (a so-called «recess pocket») to make space for the counter enamel. This step of the production process alone requires a CNC machine, albeit a relatively simple one.

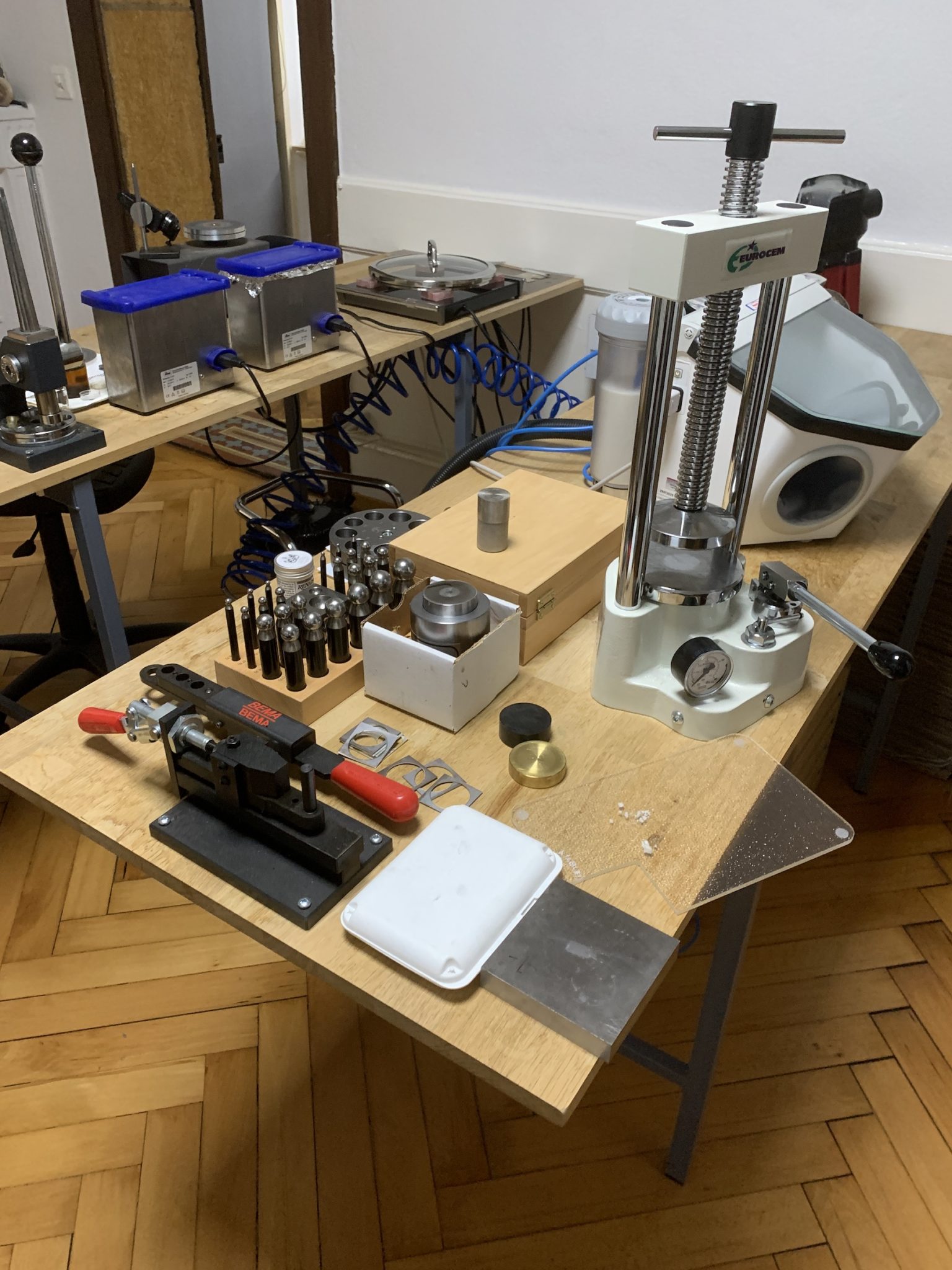

The Press

The CNC

The dial is then flattened precisely and subsequently put into the oven – without enamel that is. If you burn the silver in the oven, it gets a black surface, which you certainly don’t want to be the basis of your enamel. So the dial is put into the oven and subsequently cleaned with acid. After repeating this three times, the dial is ready for enamelling.

Oh, wait, actually not.

Every dial needs the mounting of feet. Normally (with brass dials) these are simply soldered onto the back of this dial.

Here this is not possible, as the solder would simply melt later in the oven. So Bastien has to plasma-weld little silver wires onto the back of the dial! You can see the result in picture 5.

The acid bath to clean the silver dials

And we are still not ready for enamelling.

Some colours even react with silver and hence require a golden basis, so a gold foil has to be applied (glued together via a thin extra layer of enamel) to the silver dial for some of the dials.

A finished red enamel dial next to a raw dial with the gold foil applied

Finally, we now can talk about enamel.

To start with, please compare picture 1 with picture 10, which shows two of Bastiens work benches. Hundreds of years later, fine enamelling still starts with mortar and pestle and a palm-sized chunk of special glass. You can buy enamel powder off the shelf which is fine for many applications, but if you want to offer different looks, there is no easy way.

Bastien crushes and mixes the glass by hand. Even though this might sound demanding yet straightforward, it certainly isn’t. You have to achieve just the right grain size, and although you want to have the powder quite fine, the «dust», which is caused during this process, needs first to be eliminated, in order to prevent the final enamel to get cloudy.

In picture 11 you can see two blue dials which look completely different though. The reason being, that they are based on both blue, but different structured enamel powder. The small jar contains the glass for the watch on the left.

one view of the workshop

different versions of blue dials with the raw glass and the enamel powder

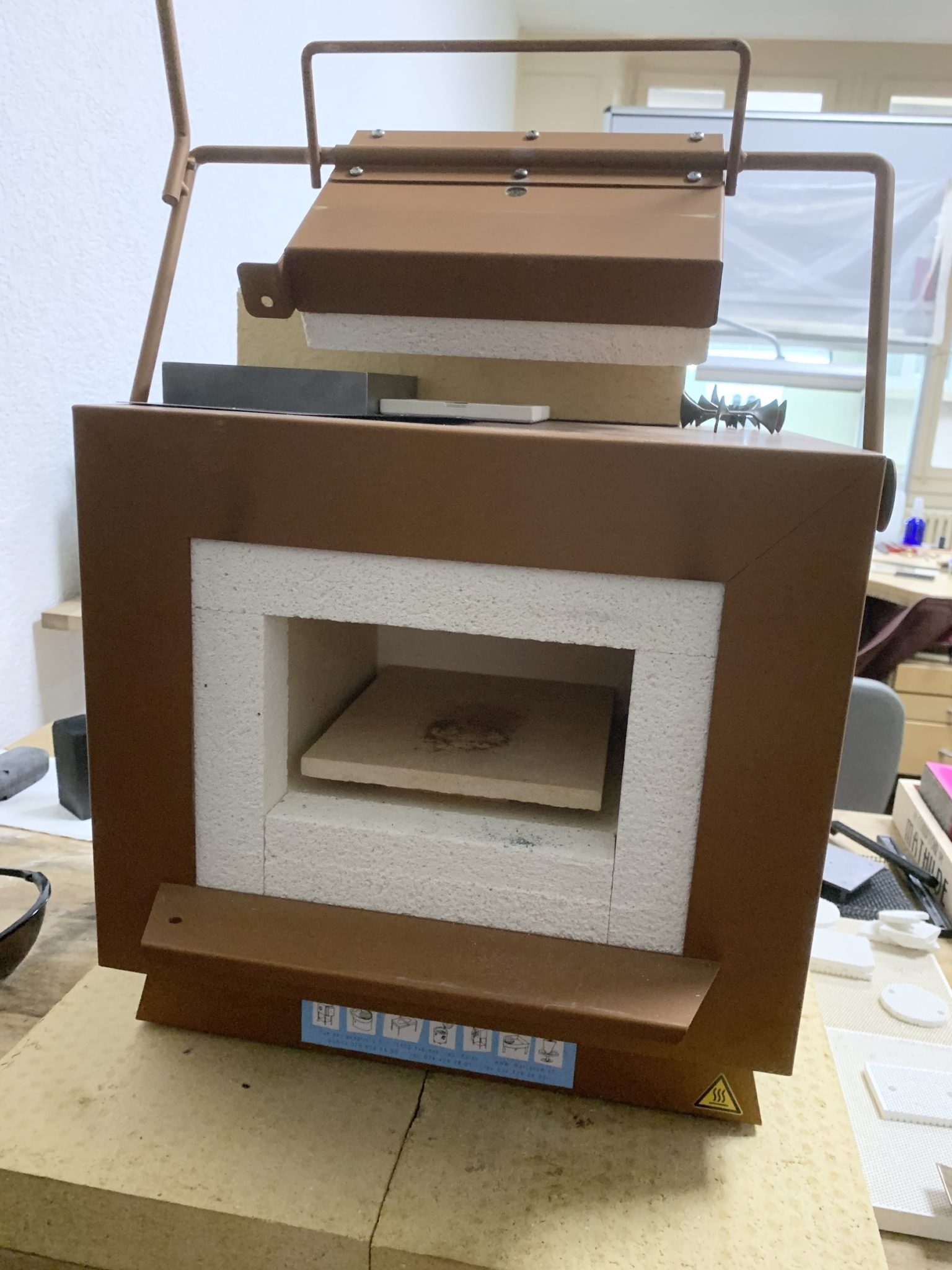

When the dial is prepared as described earlier and the enamel power is ready, well, then finally the enamel can be burnt. The oven itself is actually surprisingly small and also the burning process only takes a few minutes. The duration however is crucial and must not be too long or too short – and nobody tells you, when it’s perfect. It’s a matter or experience … and of a peek through the very small hole in the lid which you can see in the first of the oven pictures (just under the screw).

the oven

the oven

In picture 14 you can see not only my favourite watch from Lundis Bleus, but also the «dramatic metamorphosis» which the heat of the oven triggers.

my favourite: a «glittering» orange dial with an incredible «depth»

Using different mixtures of enamel powder, leads – as you could already see – to a large variety of colours, looks and structures of dials.

But Bastien goes one step – well actually some leaps – further.

multicoloured dial realised in cloisonné technique

Although 1,000s of years old, the so-called cloisonné technique is regarded as the supreme discipline in enamel making. Especially if you take the tiny size of a watch dial into account.

Cloisonné is, according to Webster, a „style of enamel decoration in which the enamel is applied and fired in raised cells“.

The cells separate different areas of contrasting enamel glass resulting in a complex picture consisting of multiple (Bastien has so far realised up to 15 in one dial!) colours.

The «cells» of Lundis Bleus watch dials are formed by a gold wire. This wire is not round but rectangular (so it looks and acts like a «wall») and measures only 0,4 x 0,1 resp. 0,4 x 0,05 mm2, depending on the complexity of the picture.

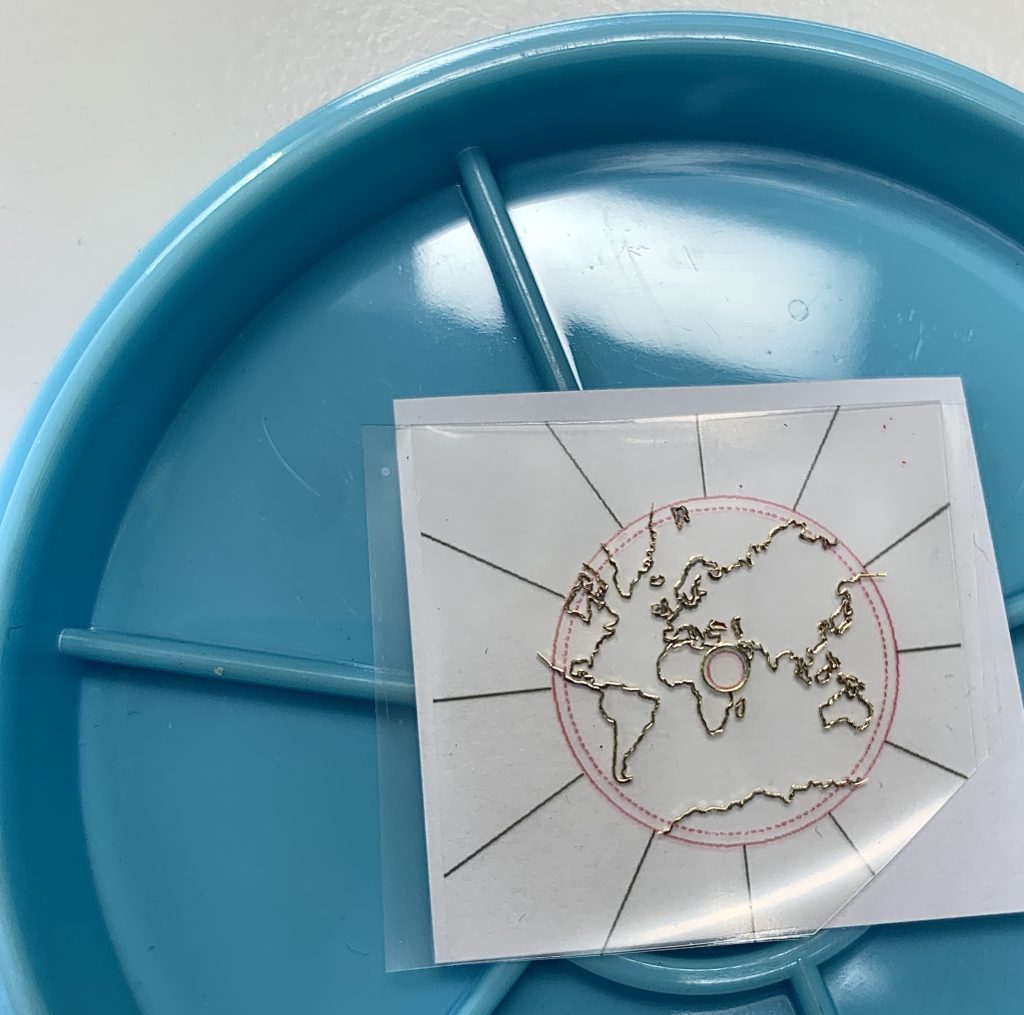

A world map ready for cloisonné enamel

A world map ready for cloisonné enamel

This work – the setting of the gold wire – is understandably done under a microscope. You can see it here in the so-called laminar flow workbench, which keeps the working area dust-free (as a side note: these are also manufactured in La Chaux-de-Fonds; also please note that the lamp lying on its side is not standard, this was only for me to make a picture;-)). There is no further explanation needed to see, that this is a challenging task, which you can only do if your «concentration level» is 100% …

Laminar flow bench

Laminar flow bench

As you don’t want (thick) soldered joints or, even worse, gaps (where the colours would mix) the whole of the American continent on picture 16 is only one piece of wire!

And so that it does not become too simple, the whole wire structure has the be heated from time to time to get rid of internal tension and also has to be flattened every once in a while, too.

Easy to comprehend that this «wiring» part of the work alone can well take a whole month or more.

I was allowed to have a look on one of his current projects, an endemic animal of Australia; I am a) not authorised (as it is a customer specific project as opposed to a world map which is inherently open source) and b) not able to explain this here in more detail, as my head would explode:-).

a finished cloisonné dial (taken from the IG account of Lundis Bleus)

a finished cloisonné dial (taken from the IG account of Lundis Bleus)

Finally also the printing of the indexes, logo etc. is made in-house. This also takes place in the laminar flow area with an old-fashioned yet highly professional pad printing machine (left to the microscope in picture 17). The pad picks up the special ink from a cliché, which is basically a metal plate with a finely etched image of what is to be printed, i.e. transferred to the dial.

Bastien carefully repeats this process several times, to achieve thick, slightly «3-D-ish» indexes.

The Fine Print

After all this you might think now „Why such a big effort?“

My personal answer to this is: control; control and flexibility.

Unlike other brands, Bastien does not offer one or two enamel dials, but rather a huge variety of different styles and looks as well as custom versions. Things like this are only possible by not just doing the standard procedure …

To conclude, a few words about the delivery times.

For a model like the orange or the light blue (so called «Color Spectrum Collection»), with a regular strap like on the pictures, one must count 6-7 weeks.

For a «pièce unique» cloisonné enamel, it is at least 5-6 months, but could easily go up dependent on the complexity and his workload.

All other models are between these lead times… so basically from 6 weeks to 6 months.

And now, to complete and round off the whole thing, a few random impressions of his workshop and surroundings:

PS: did I mention, that Lundis Bleus also makes dials made of rare and precious stones and meteorites? Well this is another fascinating story …

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.