Kieser Design is a relatively new brand from Frankfurt, Germany, producing watches, which don’t look like your average timepiece.

To make the best use of this article, have a look at https://en.kieserdesign.de first, to get an impression of the kind of watch we are talking about. The basic idea of Matthias Kieser designing this watch was „more colour“. So you can configure your watch using a variety of colours for various parts. However, a major challenge had to be faced: to maintain the immaculate look of a coloured case throughout the years you have to protect its surface somehow. The Kieser Design watch, the «tragwerk.T» does this using a kind of exoskeleton, inspired by a dragonfly.

Nearly every component but the movement and the strap is made in-house. You might expect a more traditional watch if you hear this, but his first watch, the «tragwerk.T» is actually a very modern looking watch.

As I am living in Frankfurt, too, Matthias Kieser opened his doors for us to have a look and experience what makes his watches so special.

This article is probably different to most brand or product descriptions or owner interviews you have read so far. I will omit the design phase and why the watch is designed and constructed the way it is. You can read this on the website of Kieser Design.

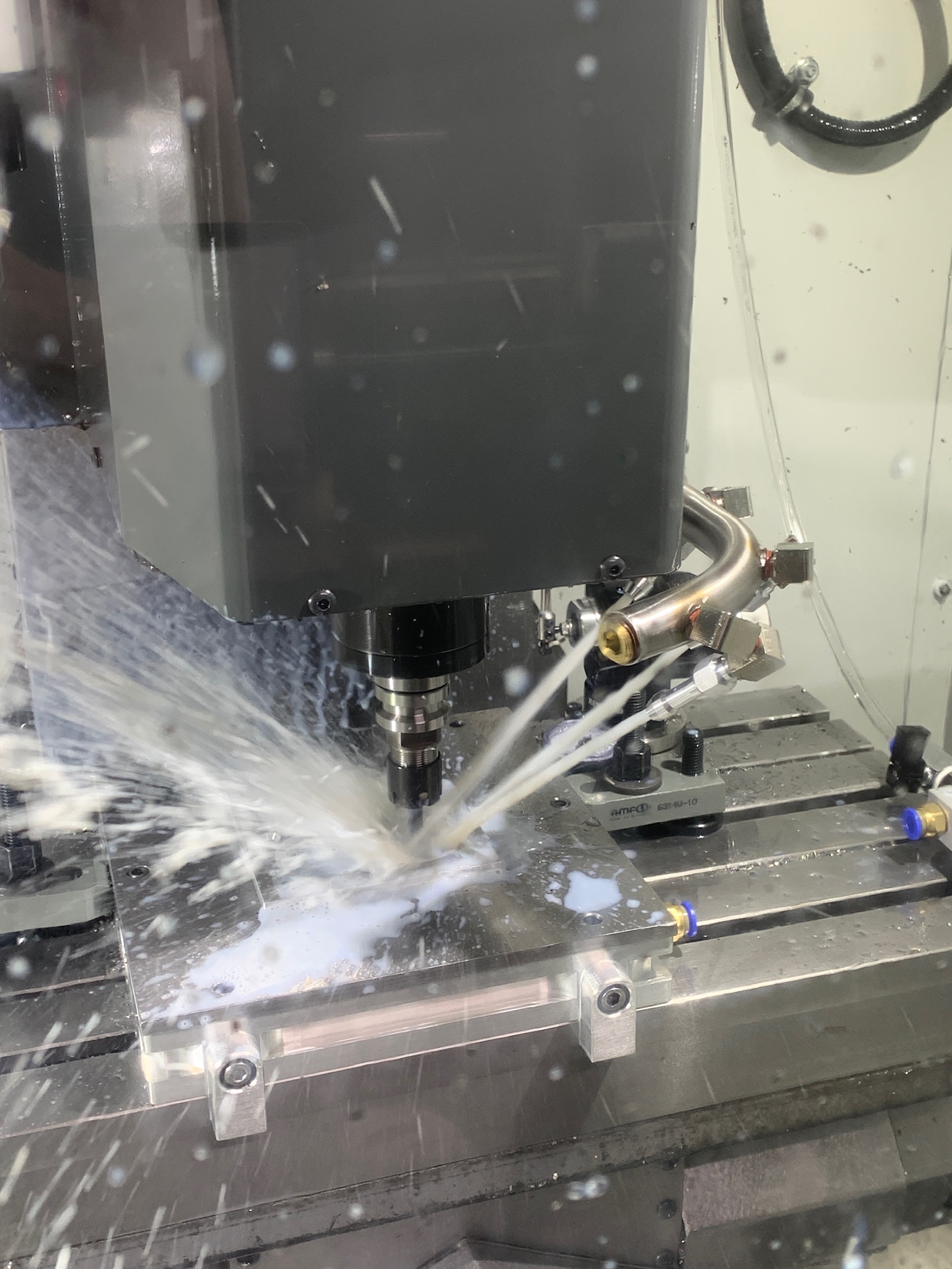

In this article, I try to describe the process of how Matthias produces a watch – step by step from start to finish. I mean the real stuff in the workshop, not at the drawing board … my goal is for you to smell the coolant fluid while reading this article.

It all starts with a raw bar of titanium.

As you can read later, an extraordinary amount of work is done in-house at Kieser Design. However, cutting the bar into slices and drilling holes in it does not require a very high amount of precision, but sheer power. So this first step is actually done down the road from Matthias’ workshop before the titanium rings are machined on the modern CNC mill.

With a few exceptions (which we wll talk about later), there is no need to send production drawings or parts to manufacturers somewhere else on the globe or even only downstairs to the guys in the factory, as Matthias does them by himself.

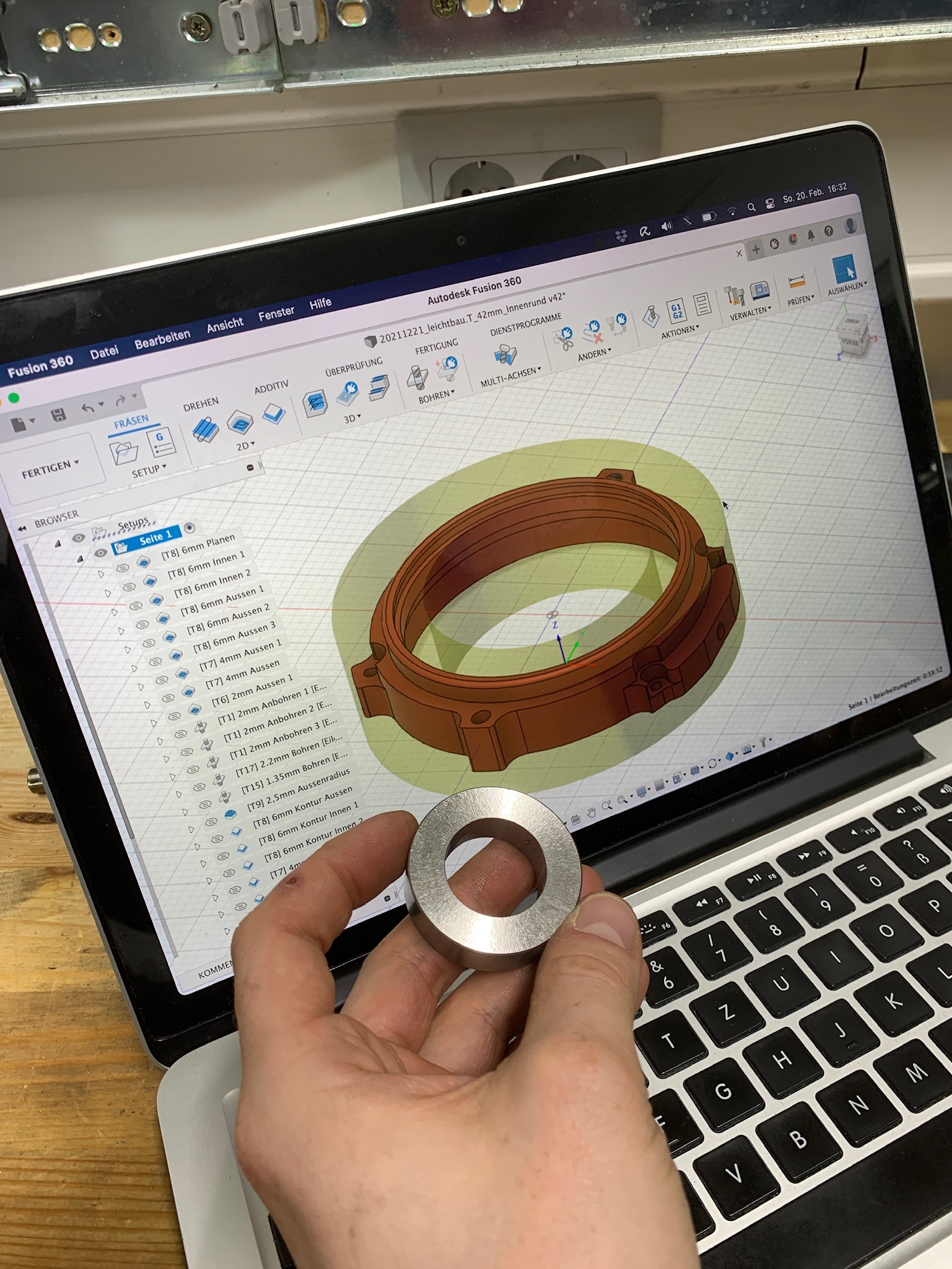

The milling programs are derived from the CAD drawings and then transferred from Matthias’ laptop to the CNC machine.

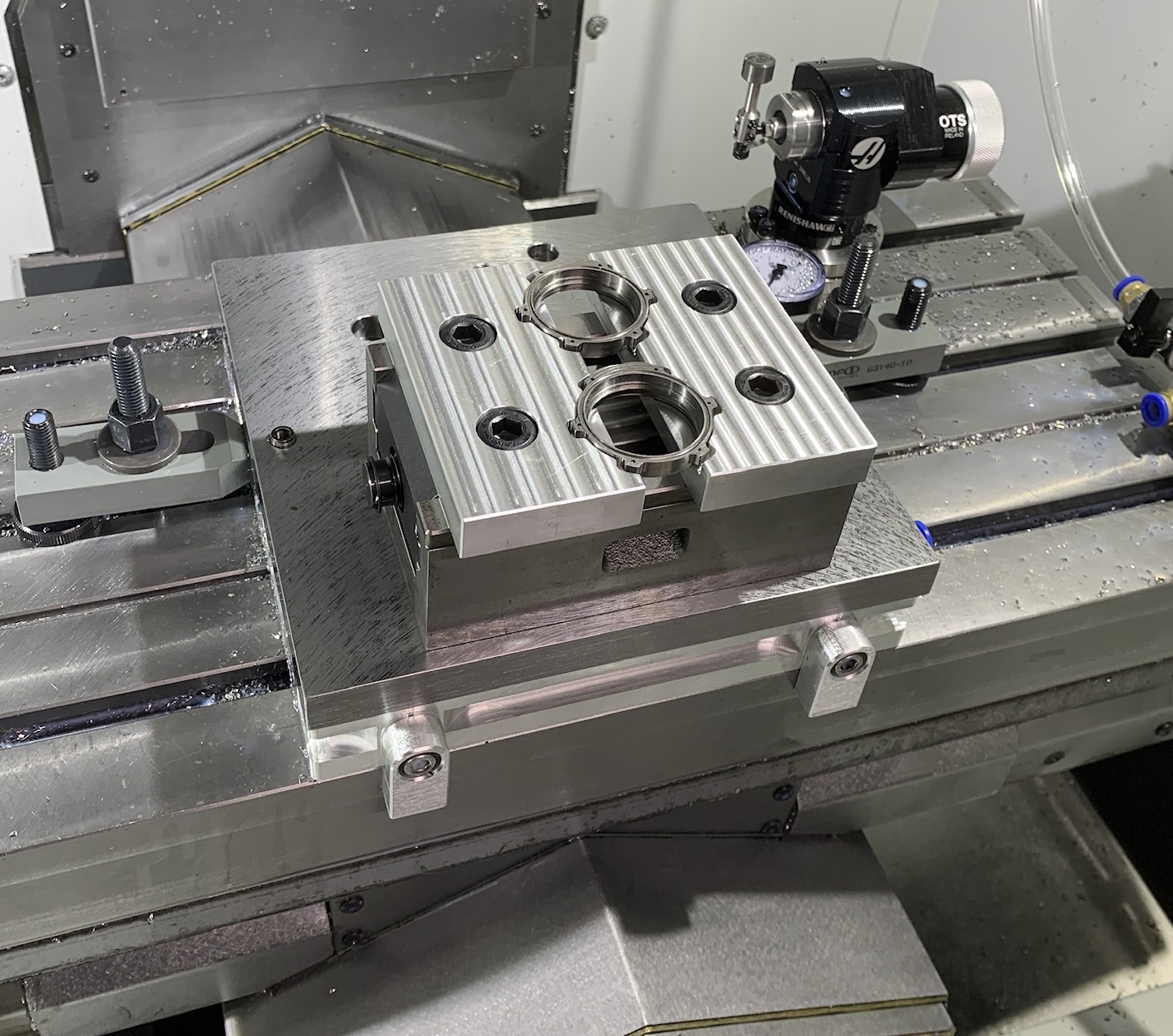

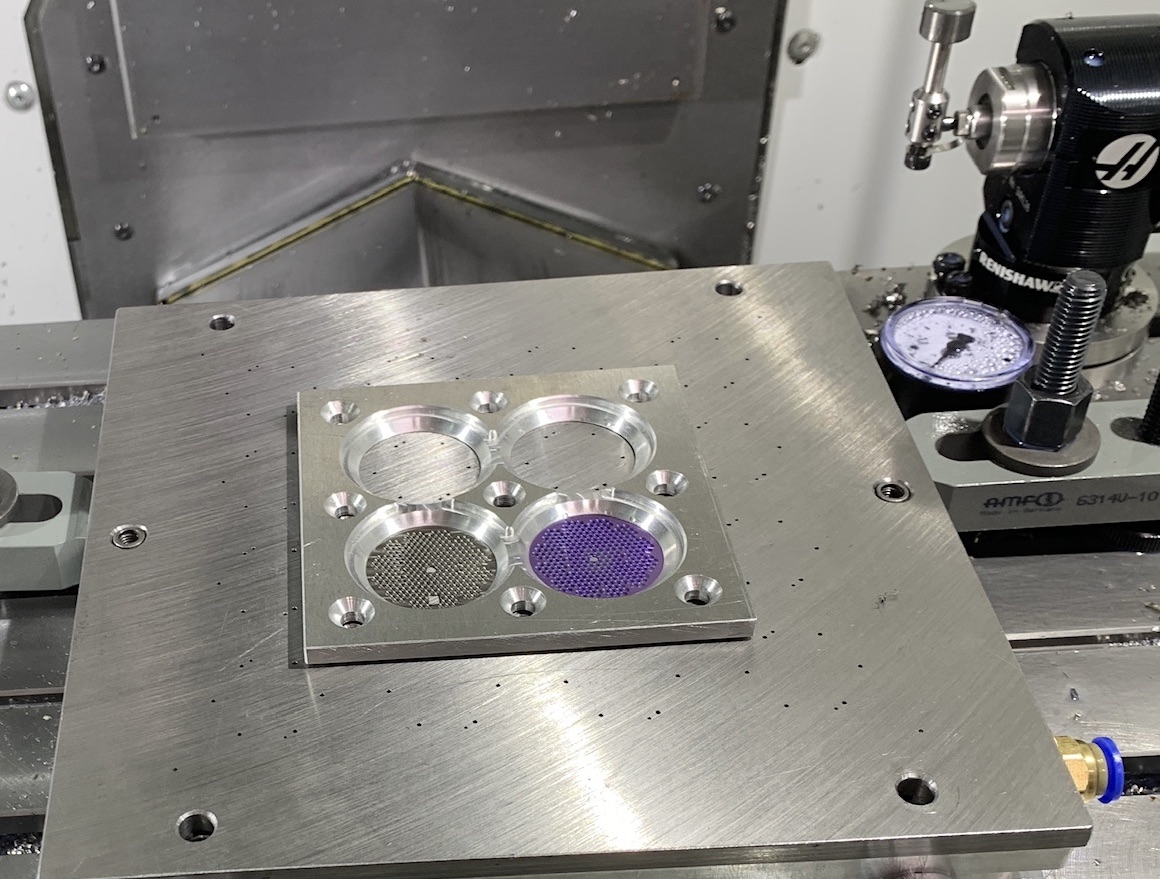

The CNC does not only mill the complex and comparatively large (inner and outer) cases, but also the very small indexes and date windows as well as – maybe not most importantly, but most visually – the dials.

The endmill cuts down into the titanium disk 287 separate times to create the mesmerising honeycomb–structure.

(Just for demonstration purposes we put a coloured dial into the machine, the anodising is normally done in a later step.)

This dial structure, together with the external case, may be the most important parts defining the unique look of the watch.

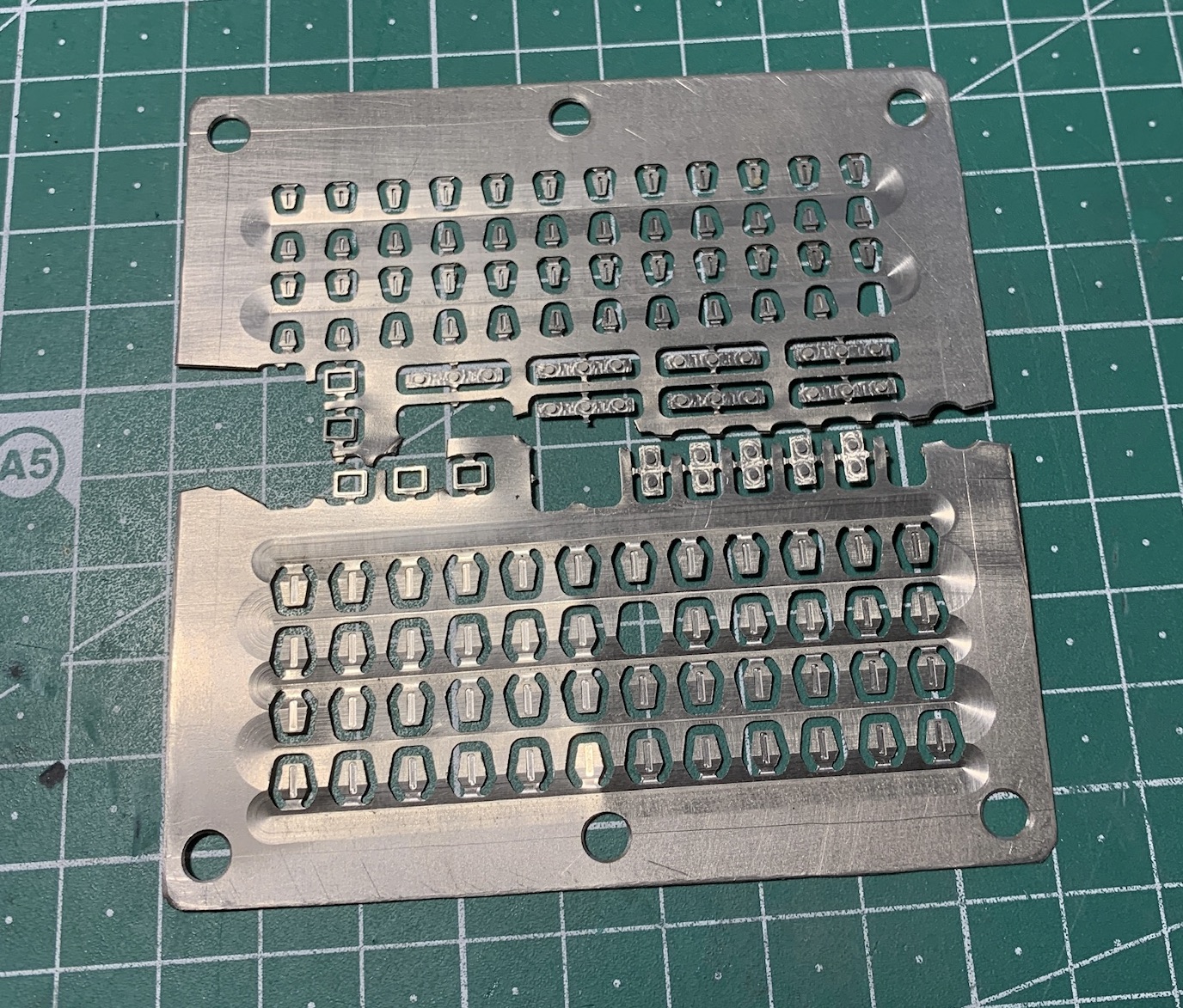

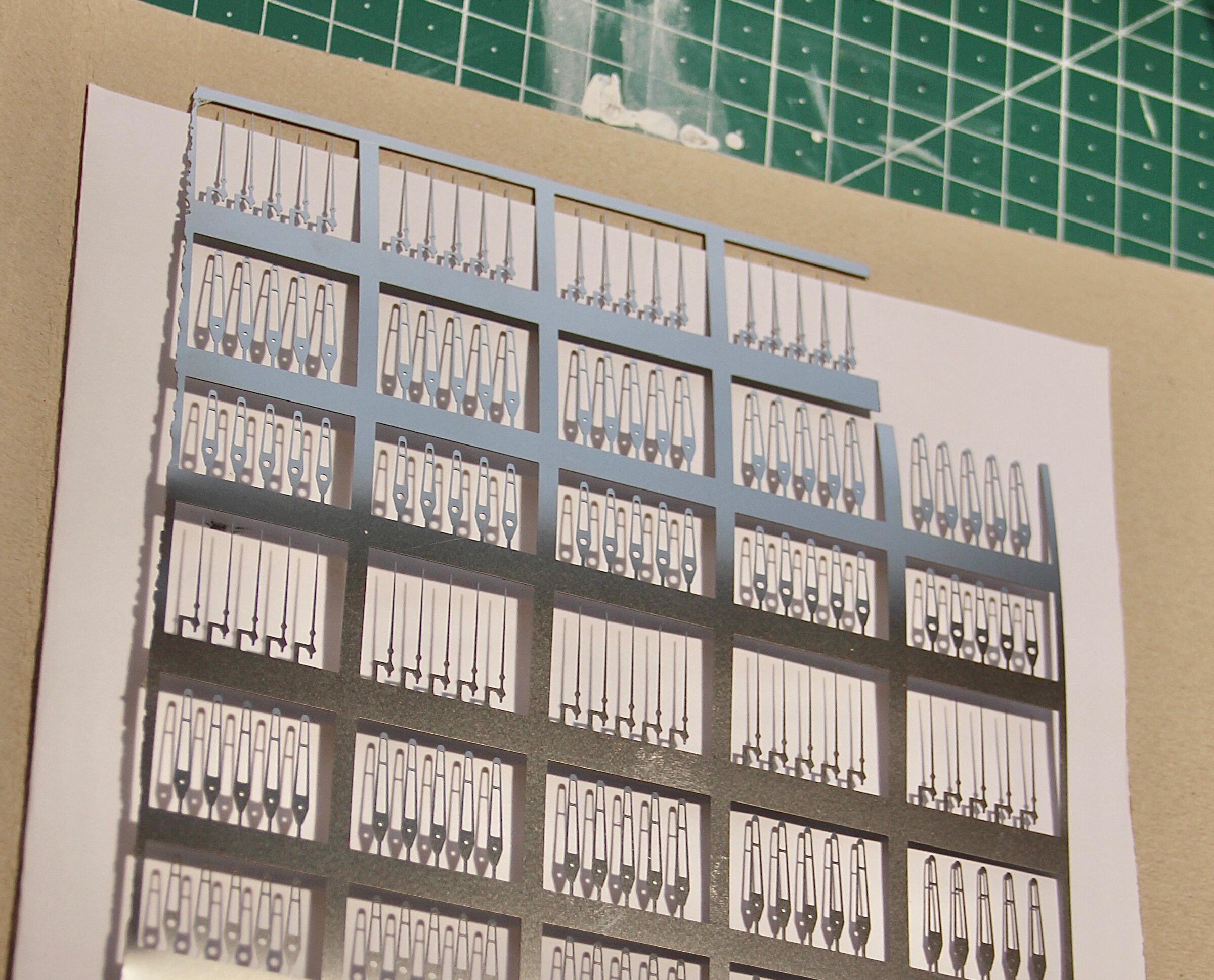

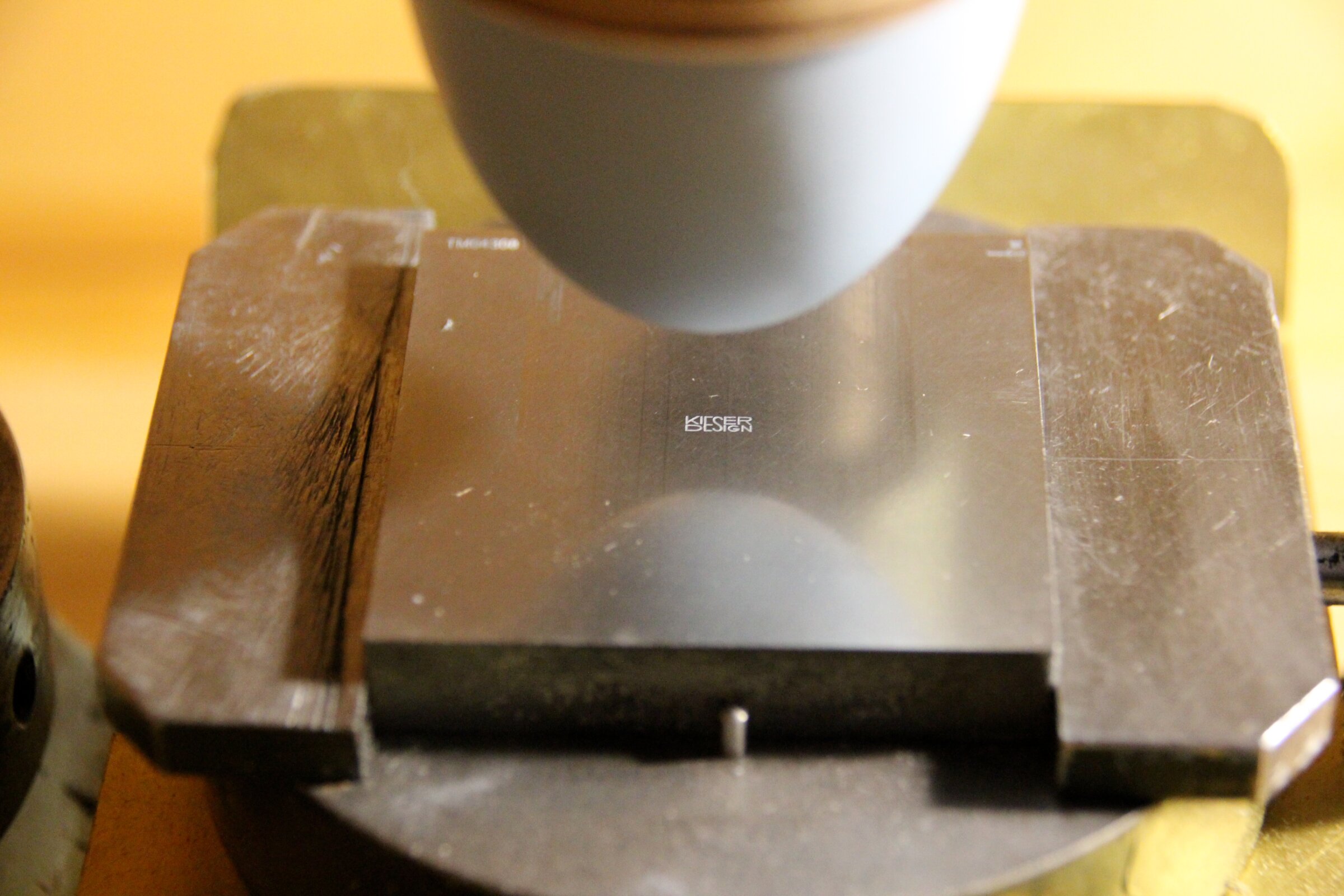

The indexes (there are large and small ones), the date window frame and the plates for the brand and model names («Kieser Design» and «tragwerk.T») are machined from a titanium «sheet» in one go, the result is a plate which reminds me a bit of the runners which were in the boxes of the model planes I used to assemble as a child.

From where we are now in the production process, you might ask yourself: Is a watch «handmade», when CNC machines are used?

Well, a guilloche dial made on a 100 year old manual machine is something very adorable. But if the whole watch is made in-house by one guy or maybe a handful of people in the future – as it is the case with Kieser Design (pun intended) – CNC is not only indispensable from a commercial point of view, but above all from a quality point of view. Especially given the complexity of the tragwerk.T-case. This would be merely impossible with only a traditional lathe! And as you will see, the manufacturing process is pure handicraft from now on!

Despite all the accuracy and precision of the CNC-machined parts, there is still a lot of finishing to be done, and this is where the real work starts.

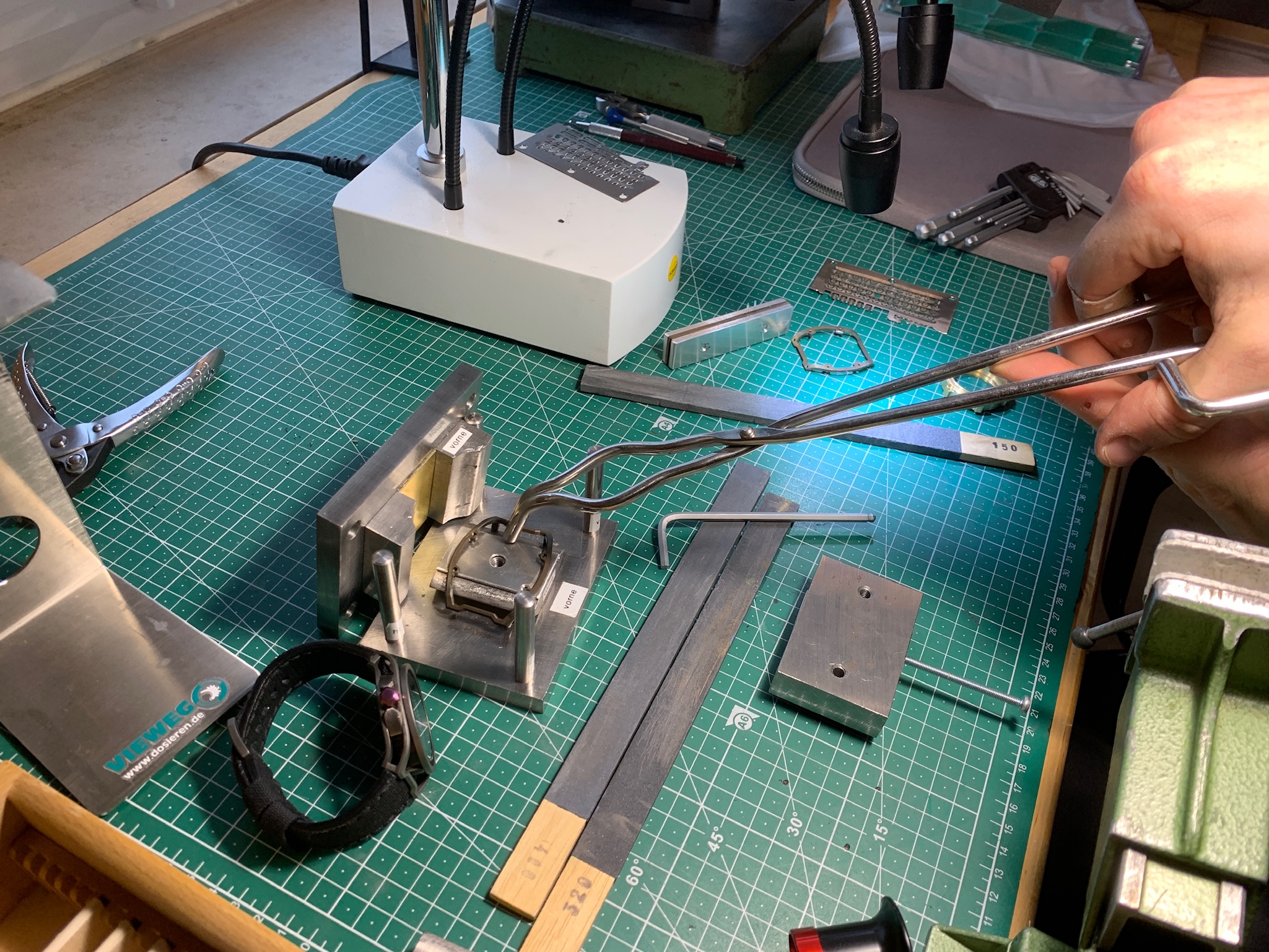

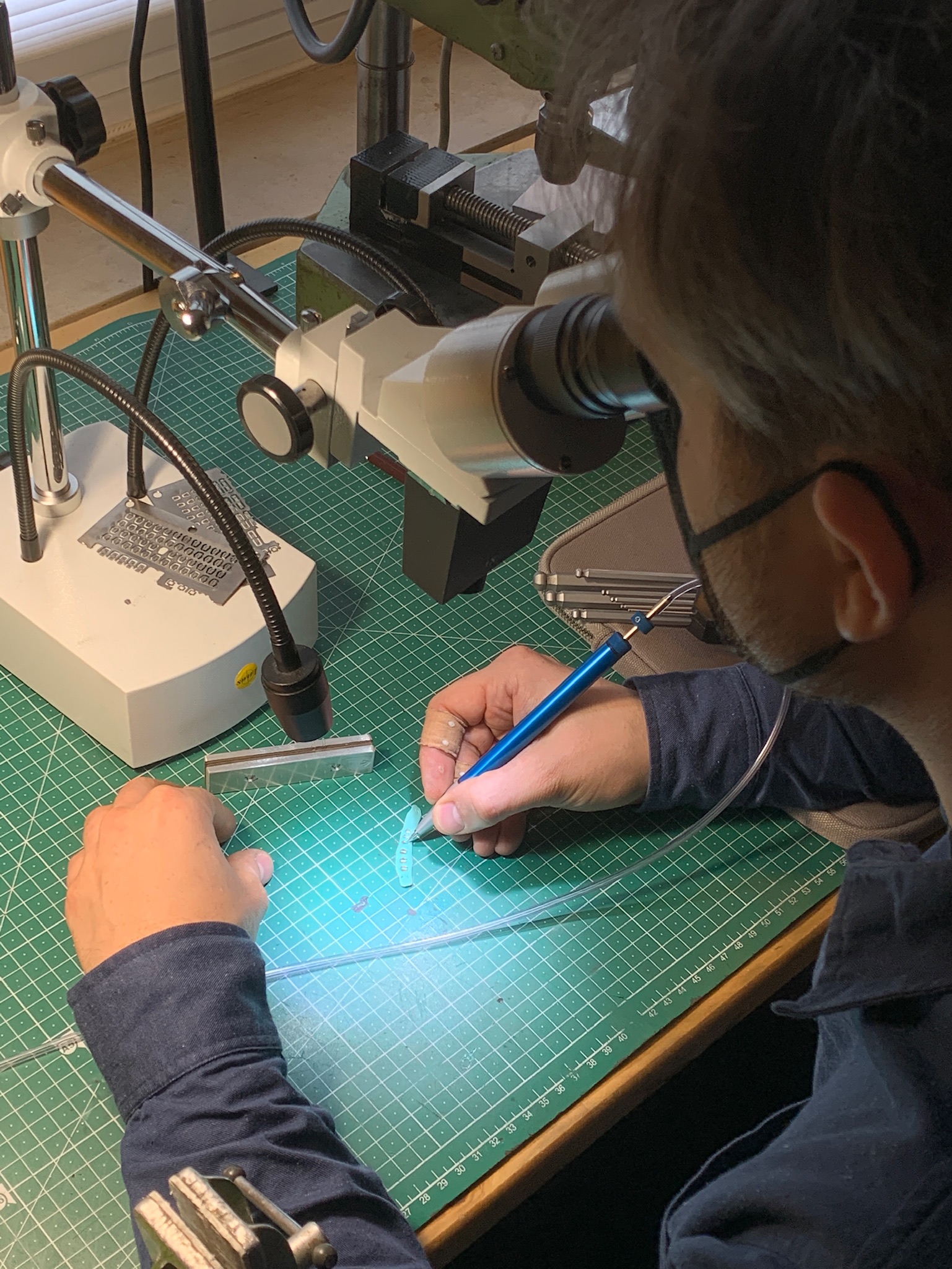

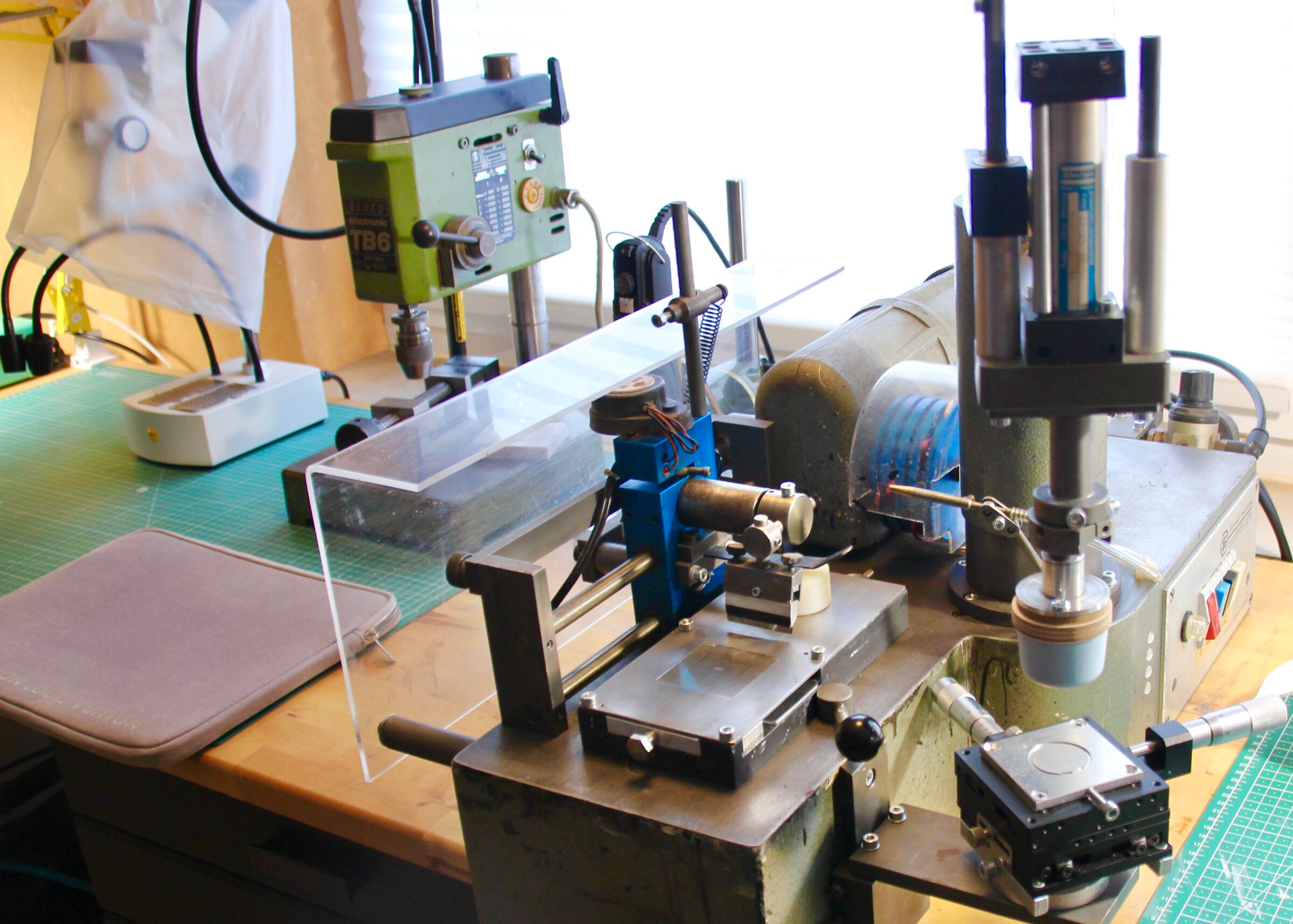

As you can see Matthias uses a broad mix of tools ranging from very modern equipment (i. e. the CNC machine), old mains-powered machines, ancient manual apparatus and of course completely manual tools such as pliers and screwdrivers.

He even constructs his own tools, when needed. We will cover that during the following production steps.

(NB: of course, the watch is not built in the order I am describing it here. Obviously, he makes always a batch of cases, a number of indices etc. at a time; the order in this article is merely a rough guide describing most (not all) of the steps necessary to get from the a. m. bar of titanium to the final watch)

The top and the bottom part of the inner case are machined with high precision, allowing them to kind of «click» together (later, of course, screws come into play), so after Matthias polished them you can hardly see the transition between the two.

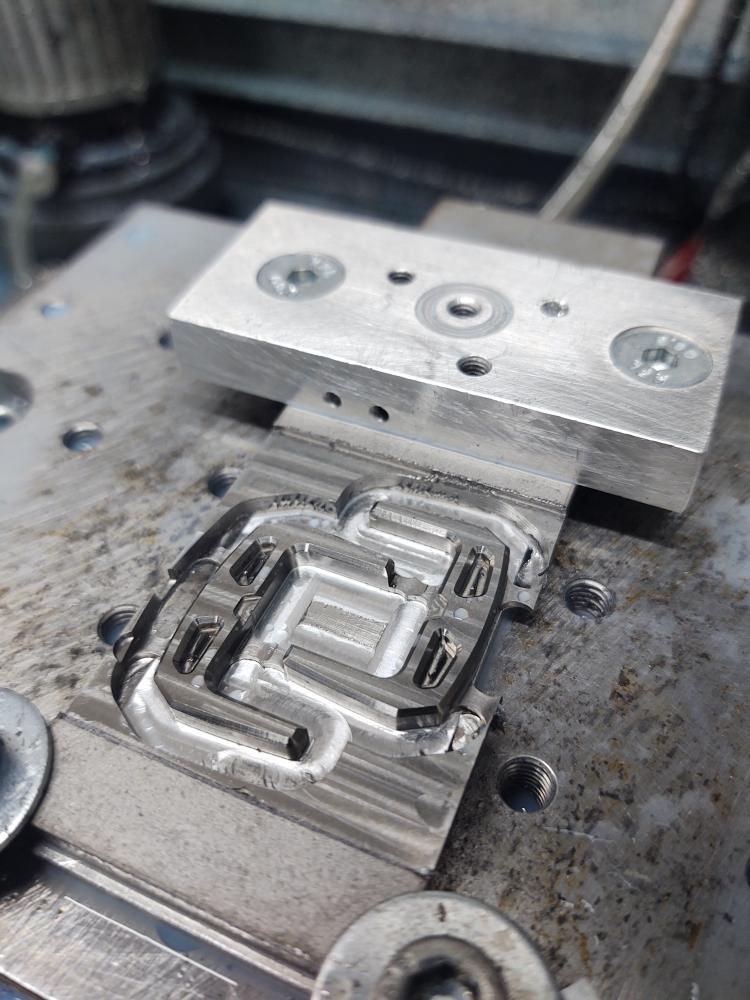

As mentioned before, the «tragwerk.T» uses two cases: the inner case (which houses the movement) and the outer «exoskeleton», which protects the coloured inner case from scratches. This outer case (again an upper and a lower part) is first milled by the CNC, then heated in a special oven and subsequently bent into shape using a special tool and a manual press.

The last two pictures are posed, in reality the parts have to be taken out of the oven, placed into the tool and then pressed very quickly.

The tool is obviously a special design and also made in-house.

Following this, these parts are first sand and then bead blasted to achieve the clean and technical look of the end product (NB: the following pics show the parts before sand/bead-blasting)

So the external case alone goes through quite a number of some manufacturing steps: it is first CNC machined, then bent using heat and pressure, then fine-adjusted manually and at the end blasted.

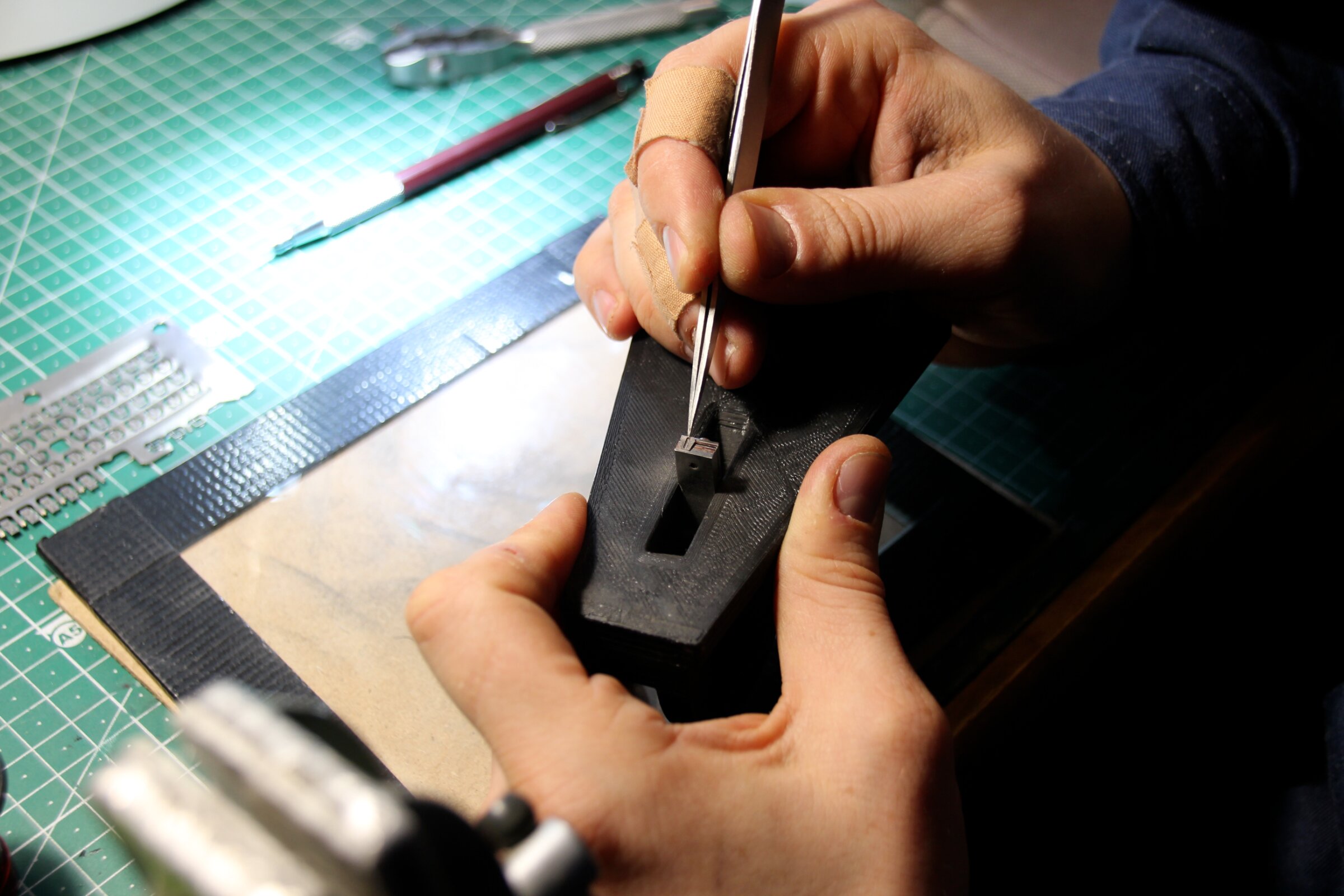

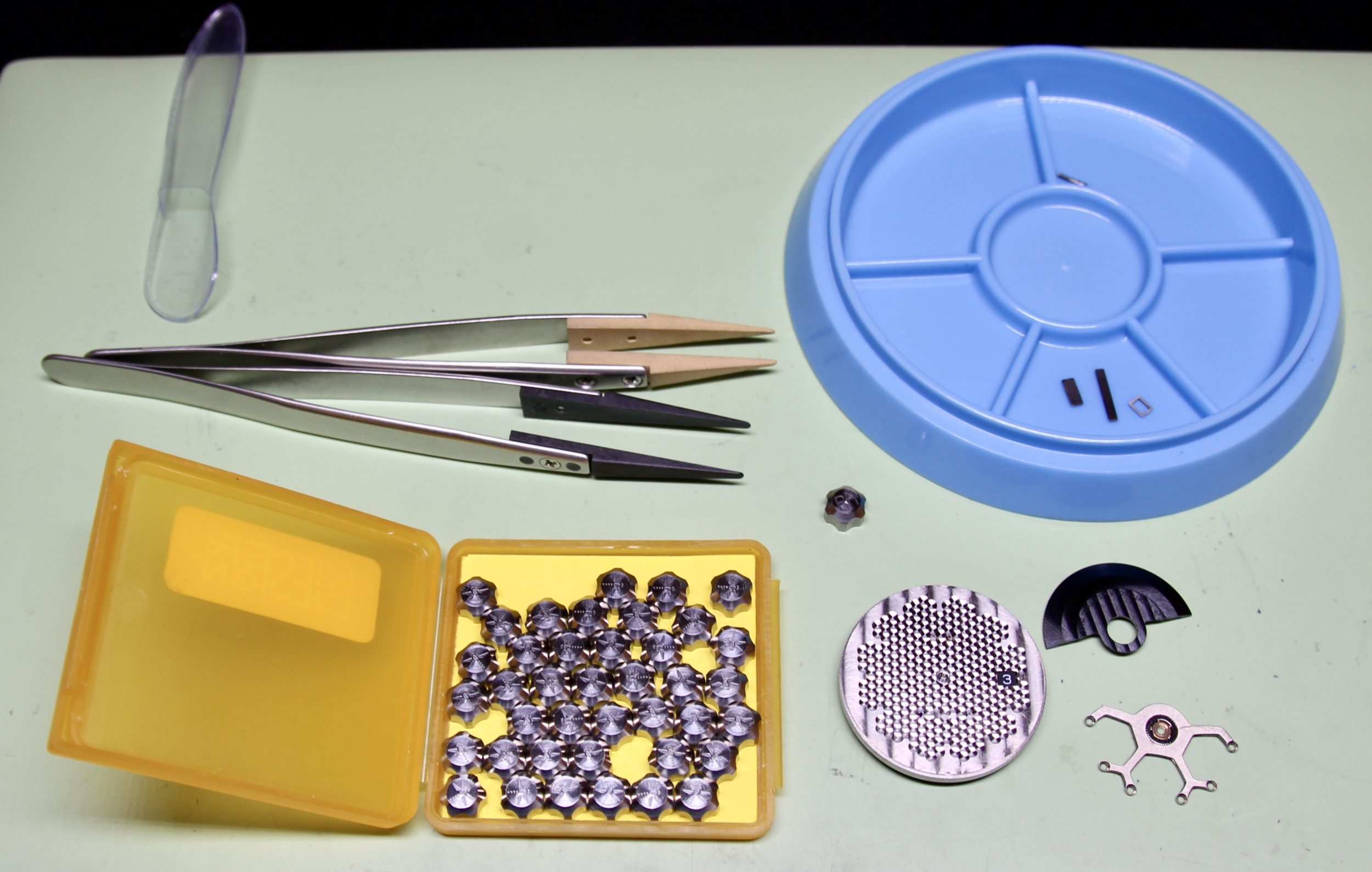

Back to the CNC machined small parts which later are to be applied to the dial (see above: picture 6). In this rough state they can of course not be used directly. All these tiny titanium pieces have to be deburred and polished. This is obviously a difficult and delicate job, as these parts are really small.

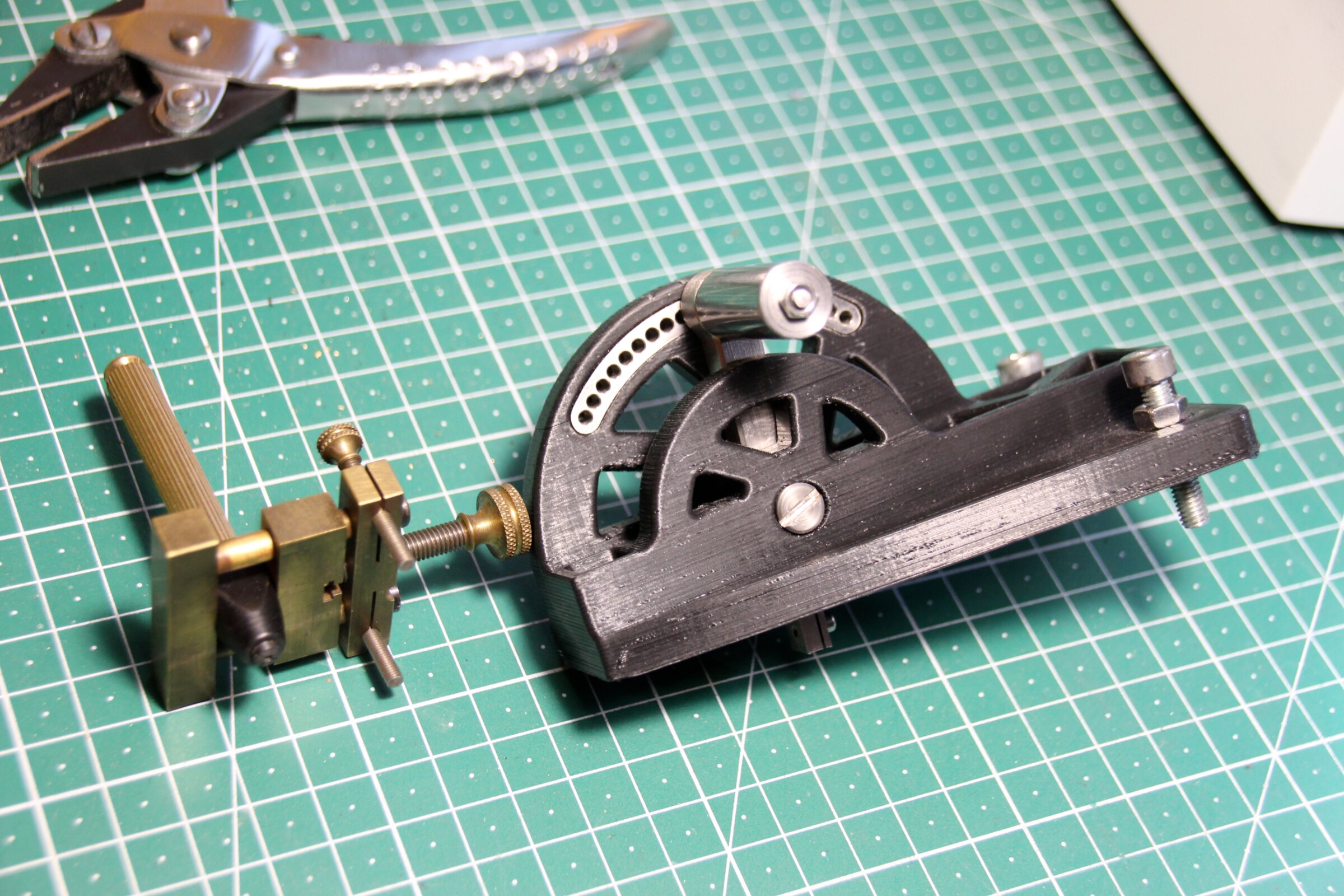

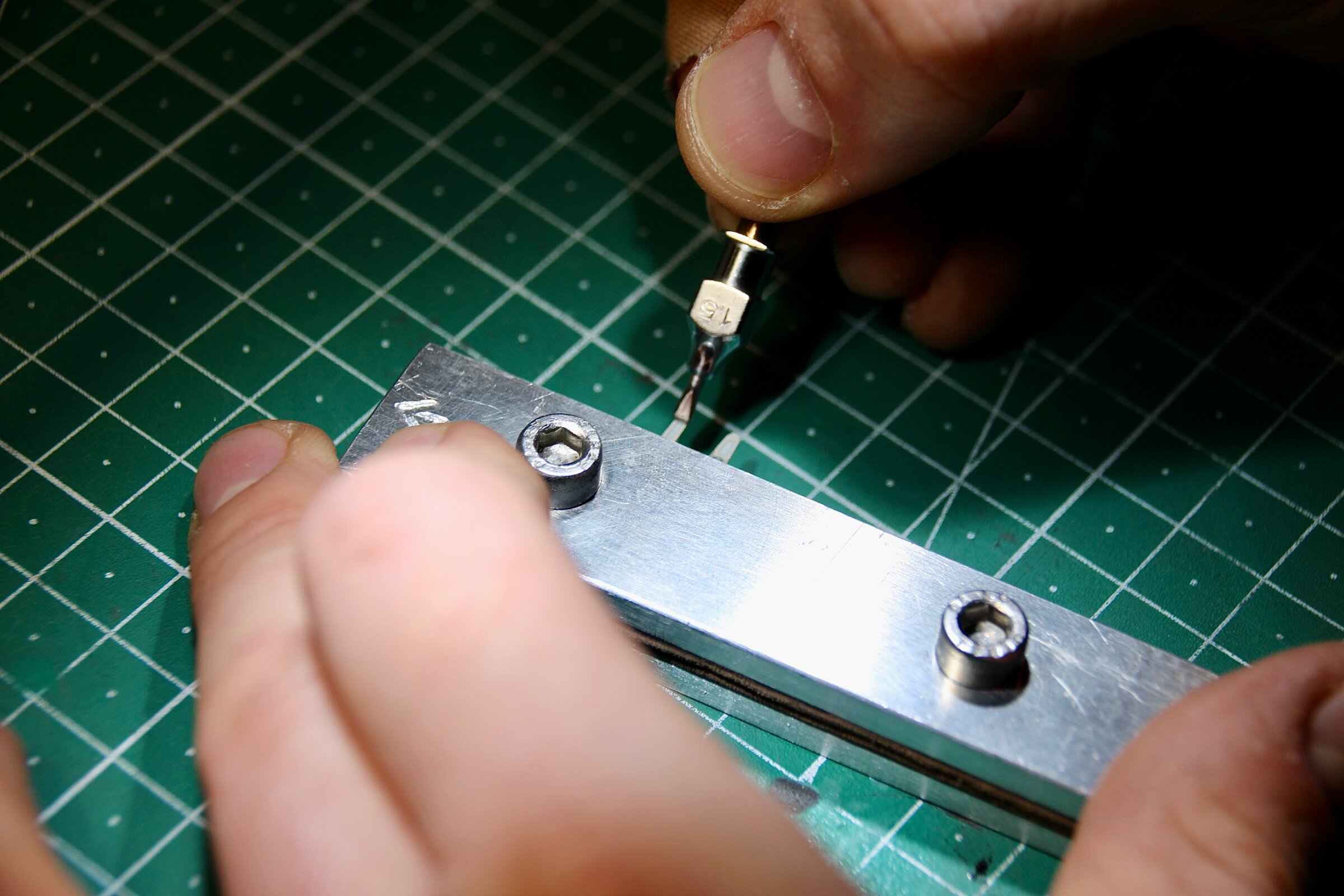

The main problem for Matthias was how to handle such small parts (down to 0,15mm in thickness in the case of the logo plate). While Matthias uses the ancient brass tool on the very left of picture 15 for polishing screws, he couldn’t find anything to polish the main surfaces of the indexes. Especially as the large and the small indices have their top surfaces tilted in different angles (5 resp. 10 degrees).

So he constructed his own tool, which he produced using a 3d-printer and CNC-machined parts.

The index is placed in the «finger» of the tool, the appropriate angle is set and then the surface is polished on diamond micro finishing films on the bench.

Even the pliers he uses for the completely manual polishing are modified using cordovan leather, which proved to be ideal for handling these parts.

The hands of the watch again come on a similar «runner-like» sheet, but they are – as they are even finer than the date window – micro-etched from stainless steel.

So the hands are delivered by a specialised partner according to Matthias’ specifications and then finished by him in a similar way as the indexes. To get maximum precision, Matthias chose a partner company which normally produces razor blades and electronics components.

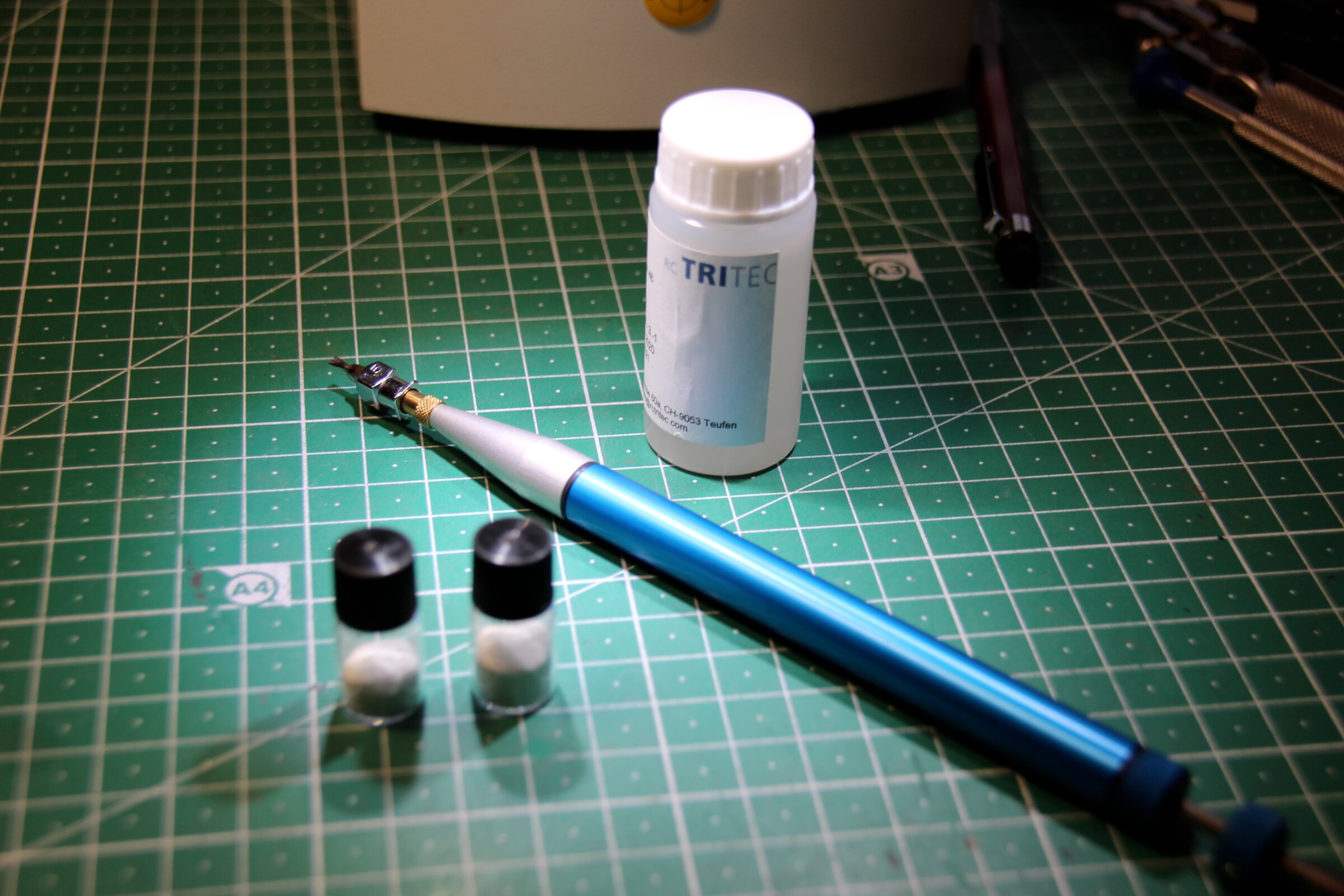

Hands and indexes are also lumed manually. This is done – after the parts are cleaned in an ultrasonic bath – using the machine far left in picture 7 showing the workbench, which makes sure exact doses are applied. Very, very little of the very, very expensive lume material is carefully and evenly applied on the holes of the hands from the backside utilising surface tension.

The hole of the dispensing tip for luming the indexes is 0,1 mm in diameter …

But it can get even smaller. To mount the hands onto the shaft of the movement, Matthias had to design custom hand fitting bushings, which he gets turned externally. These are pressed (or riveted in case of the seconds hand) into the hands using a classic staking set. The picture shows how the rotor bearing is pressed in, which is done with the same tool, but the bearing is large enough so that you can actually see something …

Also not shown here is, that the holes in the hands have to be reamed to size manually before fitting the bushings …

Maybe the most important part for the Kieser Design Watches is not described and shown with pictures here: the anodising – which allows for the colourful design.

As you can see from his website, you can have the dial, the seconds hand, the rehaut, the inner case, the crown, the rotor, the movement holder ring, and even the screws in six different colours!

But as anodising is a time consuming and potentially dangerous chemical process with harmful vapours, we skipped it.

After the anodising the rehaut and the dial have to be printed.

If you have read the above, you may not believe it, but according to Matthias, the printing is one of the most delicate tasks.

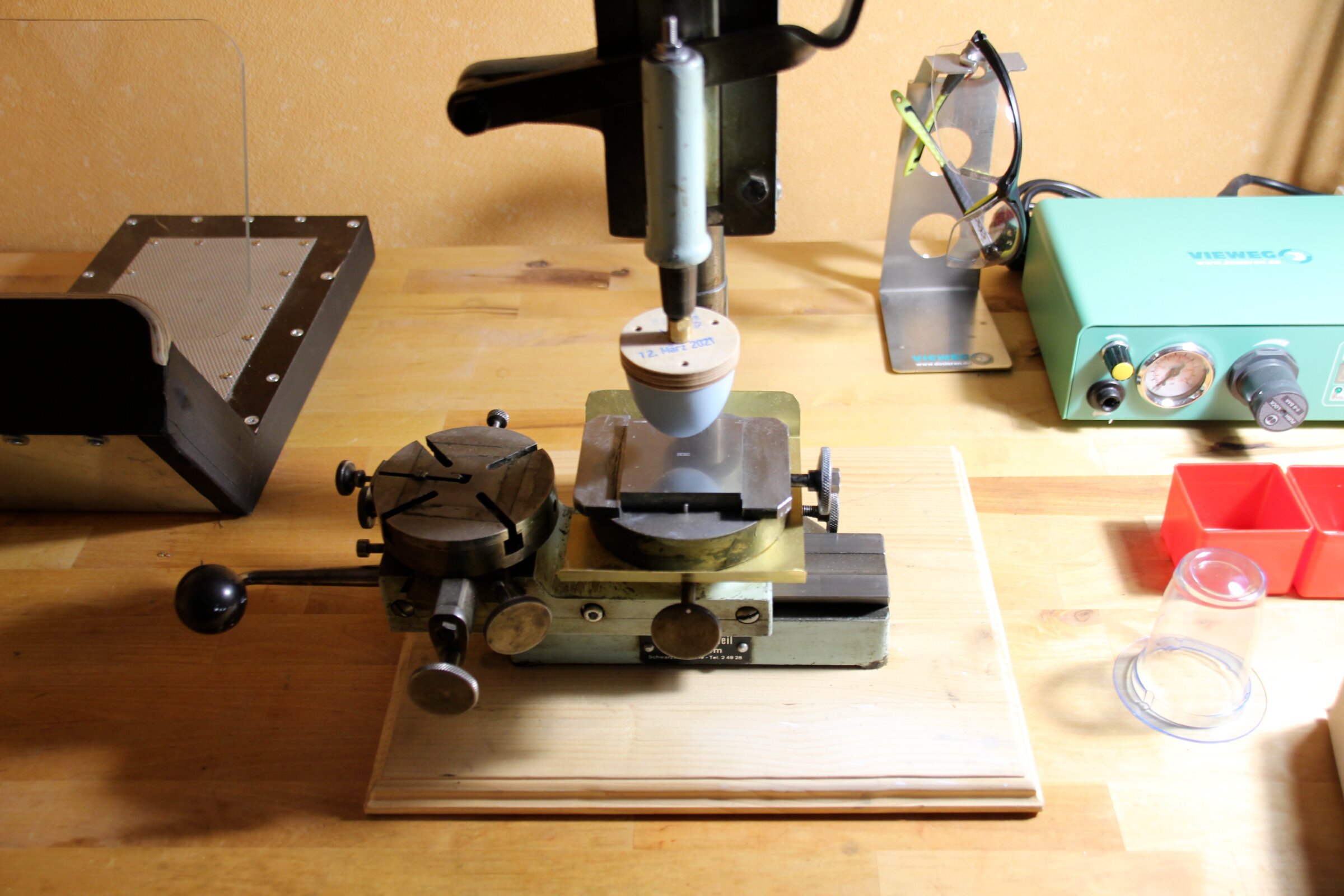

For this, he uses a semi-automated yet old fashioned machine, which he bought pre-owned (obviously) and refurbished. While still a lot of manual work is required, this machine allows constant and repeatable results.

A precision kind of blade «wipes» the surplus paint off the cliché before the pad picks up the left over paint and applies it on the dial – or rather to the small plates, which later are applied to the dial. In a similar process the the second markers on the rehaut are printed).

One last word about the dials: to mount the dial on the movement, there are usually little «feet» soldered to the backside of a brass dial. To attach feet to a titanium dial was a challenge for Matthias. He eventually found a specialist which is able to weld titanium wire to the rather thin dial.

As far as the movement is concerned, the «tragwerk.T» relies on Sellita. Where many brands just modify the rotor with some engraving, Matthias goes a step further again and constructed and builds his own rotor. Again, the shape is inspired by nature. The rotor is 25% lighter than the original. To maintain sufficient winding power, the weight is made of (heavy) 18 carat gold. Furthermore, the diameter and thus the torque of the rotor is bigger than for the standard rotor. While the gold part is cast by a third party, the titanium carrier is – of course – milled on Matthias’ CNC and finished as well as assembled together with the golden weight, the bushing etc. again by hand.

A small (M1) thread is cut into the gold weight which is finally polished using leather, cotton and diamond paste.

You also see the crowns in picture 28, which feature the brand’s symbol, the dragon fly. Or, as I could see there on a customers watch, whatever you want to see there, as this can be individualised!

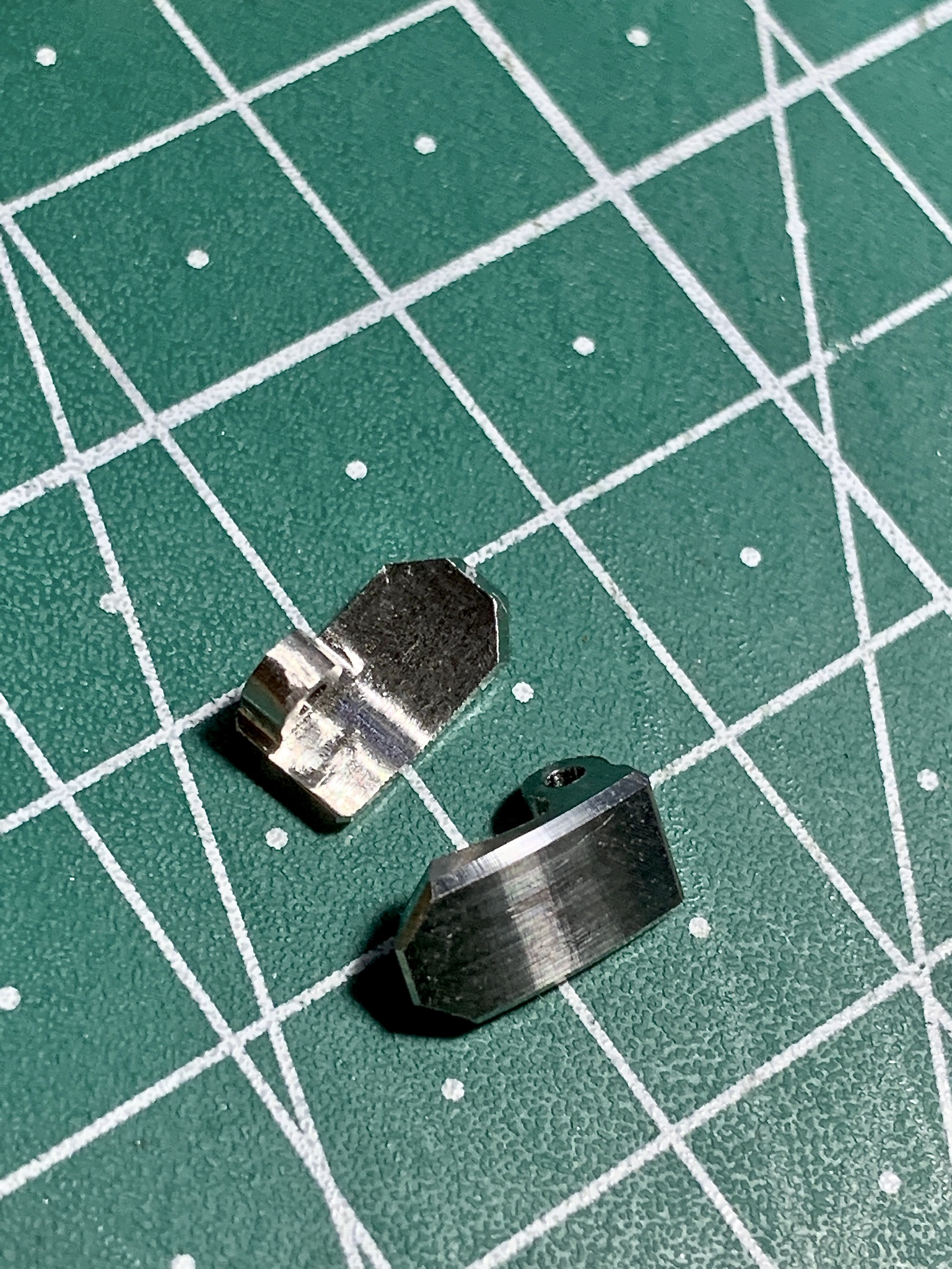

Another small, separate part of the watch is the crown guard. As this is part of the external case with the task of protecting the watch, it cannot be part of the (inner, coloured/anodised, if you choose so) case. Which means, it must not be milled together with the case, but has to be manufactured, finished and assembled separately.

As Matthias told me, this is actually the single most complex part to be milled. As you can see, even this small part has chamfered edges.

Which leads me to the last and actually maybe my favourite part of the watch, the buckle, which accompanies the really great fabric strap. The strap is, btw., fixed to the lugs with standard spring bars, so you can change it easily.

As you probably expect by now, the buckle, too is produced on the CNC machine and subsequently finished. It follows the general design philosophy of the watch and is, of course, chamfered at the edges, too.

In case you ask yourself: is Matthias a watchmaker? Well, he hasn’t made an apprenticeship as a watchmaker but is rather holding a degree in industrial engineering. But in my opinion he kind of is, as he makes as you could see, well, a complete watch by hand! For regulating the movements, he partners with a watchmaker who worked for a larger well-known Frankfurt brand.

It was a long but fun day at the Kieser Design workshop. Finally – I still did not cover every aspect – my head was already about to explode!

You may have seen the plasters on Matthias fingers, so at the end I asked him what happened. He told me, that he had to machine stainless steel the day before and that he wasn’t used to the razor sharp burrs … But why steel?

Well, Matthias is not yet satisfied with the anti-reflective coating of the sapphire crystals, so he contacted a local optic company (an industry sector with a long tradition in this part of Germany) and they are jointly developing a new coating. But to put the crystals into the coating apparatus, special stainless steel glass holders are required, so Matthias had to make them first… I think this episode summarises Matthias’ passion for his watches and the determination to make them perfect in every aspect quite well.

At the end please allow me a personal statement:

As some readers may know I am a lover of ochs und junior watches (you can read about this here, here, here and here).

(BTW: Ludwig Oechslin even owns his own CNC machines to make his prototypes by himself.)

One reason why I like them is that they are simply extremely comfortable.

Well, having now worn Matthias Kieser’s watch for quite some hours while taking photos, writing notes, walking around and drinking coffee – the usual activities during a busy day – I have to say the «tragwerk.T» is for sure one of the most comfortable watches out there!

Both @fifthwrist and @tapir_ffm are in no way affiliated with Kieser Design.

This article was not written with professional journalistic neutrality, but with lots of enthusiasm – and with 100% independence from Kieser Design or any other company.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.